The CAREsolar blog

CAREsolar at ETH Zurich

On Monday the 3rd of February, the CAREsolar workshop was held at ETH Zurich, bringing together 20 experts and key stakeholders with the aim of identifying the main challenges, concepts and good practices for decision-making around the planning and design of large-scale solar photovoltaic projects.

3 February 2025

Workshop report by Ross Wallace

On Monday the 3rd of February, the CAREsolar workshop, Creating an updated conceptual framework on the socio-ecological impacts and community acceptance of large-scale solar, was held at ETH Zurich with the assistance of the Swiss Research Foundation for Electricity and Mobile Communication (FSM). The workshop brought together 20 experts and key stakeholders from Europe and beyond with the aim of identifying the main challenges and good practices for decision-making around the planning and design of large-scale solar photovoltaic projects.

Susana Batel and Ross Wallace (ISCTE-IUL) opened the workshop by introducing the CAREsolar project and presenting findings from their systematic review of conflicts and injustices in large-scale solar deployment. They built on Bidwell and Sovacool’s (2023) argument that energy justice and social acceptance often conflict in terms of ethics, goals, and theory of change—not just in project development but also in research and policymaking. Their review expanded the scope to critically evaluate and integrate these perspectives, identifying four main research clusters which would structure the workshop and guide discussions: institutional drivers, stakeholder perceptions, impacts and contestation, and innovations.

The first thematic session, "Conceptualizing and contextualizing the problem,” featured four presentations. Rolf Wüstenhagen (University of St. Gallen) discussed social acceptance and its connection to procedural justice, distributive justice, and trust—critical for community support of renewables. He highlighted the growing influence of opposition to wind power in Switzerland, emphasizing the often-overlooked emotional factors in public perceptions of renewable energy.

Siddharth Sareen (Fridtjof Nansen Institute) presented a different view, framing solar PV as multi-sited, multi-scalar and cross-sectoral. He pointed out how, in Portugal, large-scale projects dominate with little citizen involvement, attributing the challenges not to public perception but to financial constraints, regulatory inertia, and bureaucratic inefficiencies, which often sideline environmental and social concerns. Sareen also noted that Portugal’s energy decisions have lacked transparency, and a broader societal discussion on renewable energy and land use could help drive innovative solutions like Renewable Energy Communities.

Ross Wallace and Susana Batel begin the workshop.

Ricardo Filipe introduces the Portuguese context.

Following this, Ruedi Kriesi (Solalpine) and Ricardo Filipe (ZERO) presented contrasting challenges in Switzerland and Portugal. Ruedi highlighted Switzerland’s winter energy shortfall as it phases out nuclear power, noting that while rooftop solar is widely accepted, it cannot meet winter demands. Alpine PV offers a potential solution, using minimal land, but opposition from NGOs and strict environmental laws are causing delays.

Ricardo then discussed the challenges of large-scale solar in Portugal, particularly poor public participation and environmental impacts, presenting four case studies. He emphasized the lack of meaningful community engagement, with many projects moving forward without adequate consultation. These presentations, combining expertise from both the Swiss and Portuguese contexts, highlighted one of the day’s key themes: the stark contrasts in energy justice outcomes between Central/Northern Europe and Southern Europe.

The second session focused on stakeholder perceptions and cases of contestation. Doug Bessette (Michigan State University) shared insights from the U.S., highlighting how community concerns are most often associated with process and impacts. Regarding the former, communities were concerned about the lack of information about projects, with many unaware that projects in their area even existed. This insufficiency often led to misunderstandings about project attributes, but also about who was responsible for different stages of the project life-cycle. In addition, to well-documented concerns about economic, environmental and visual impacts, Doug outlined how a divide between rural and urban regions shaped concerns about “where the power goes”.

Doug Bessette discusses his research on community acceptance in the U.S.A.

Oriana Brás presents her research on the energy injustices of large-scale solar in Portugal.

Oriana Brás (University of Lisbon) then examined a controversial solar project in Cercal do Alentejo, Portugal, through the lens of energy justice. She discussed the community’s fears of the region becoming a "green sacrifice zone," where corporations benefit while residents bear the costs. Oriana showed how these fears were anchored in Alentejo’s history of social and environmental injustices, the lack of recognition of which has played a key role in the formation of a local protest movement. Despite its attempts to contribute to the planning process with its local knowledge, this movement has not been taken seriously by the local or national authorities. Although they came from vastly different contexts and conceptual approaches, both Doug and Oriana reached similar conclusions: a just and acceptable energy transition requires systematic economic, social, and political transformation.

After these introductory presentations, the participants divided into four groups to analyse the issues in more detail. The discussions were wide ranging. A key similarity was the recognition that early engagement and transparency are crucial. Differences emerged in how groups framed key actors and conflicts, with one group focusing on financial and corporate interests, while another highlighted that local communities are not homogeneous entities.

One of the groups began by reflecting on the concepts of energy justice and social acceptance, particularly in light of the contrasting realities in Switzerland and Portugal. "We live in different worlds. If you implemented such a project [in Switzerland] the way it's done in Portugal, there would be a national outcry. The way things are done in Portugal feels like the Wild West," one participant remarked.

There was also the view that, "energy justice is part of the community acceptance equation, but the concepts themselves aren’t robust enough to capture the broader complexities." This observation highlighted one of the workshop's central themes: institutional dynamics play a crucial role in driving siting processes and are therefore key to shaping both community acceptance and justice outcomes.

This theme was further tied to the speed and scale of change, as identified by Bidwell & Sovacool (2023). It was suggested that supplementing large-scale projects with smaller and medium-sized initiatives—such as Renewable Energy Communities—could help address these challenges. However, in Portugal, a fundamental injustice exists: while large-scale projects are being expedited, smaller projects are hindered by slow bureaucratic procedures. "Without active governance from the political side, we can make progress at the community level, but it won’t be fast enough to meet the needed pace," one participant emphasized.

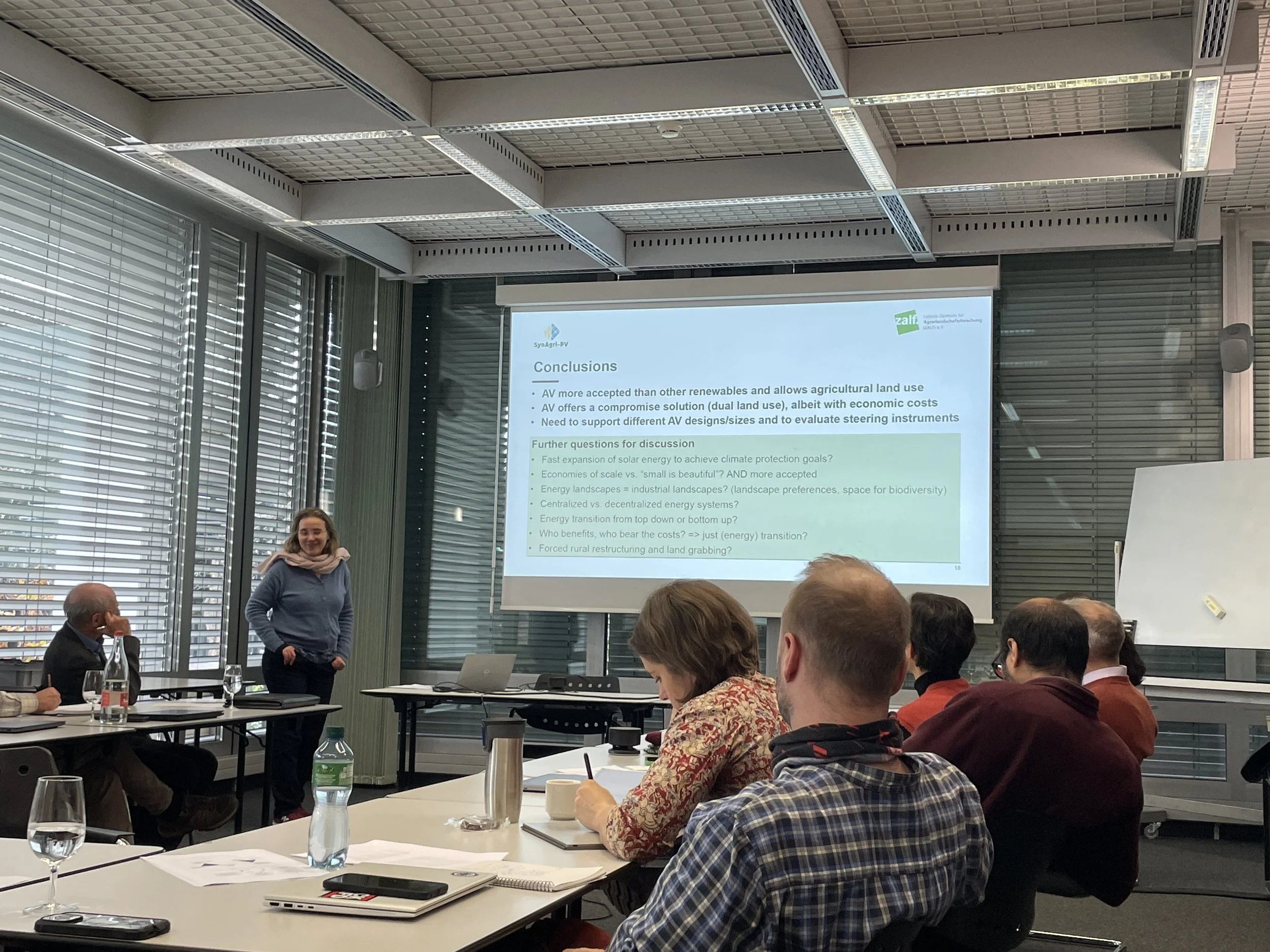

Alexandra Doernberg presents her research on agrivoltaics.

Danilo Grunauer (EKZ Renewables), Merel Enserink, Oriana Bras, Rolf Wüstenhagen and Elif Gündüzyeli in the first breakout session.

In the first afternoon session, participants explored potential avenues for more socially acceptable and equitable large-scale solar projects, focusing on emerging practices like agrivoltaics, participatory landscape design and spatial mapping tools. These innovations address energy justice and community acceptance but come with tensions and trade-offs. Merel Enserink (Wageningen University & Research) introduced participatory landscape design, stressing how involving local communities in the design process can boost acceptance and trust. She identified two key tensions: balancing local concerns with broader societal ones, and deciding whether to prioritize local knowledge or expert input.

Alexandra Doernberg (Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research) presented agrivoltaics, explaining how integrating solar panels with farming can benefit both renewable energy targets and agriculture. She discussed varying stakeholder perceptions—farmers, conservationists, and policymakers—regarding the risks and benefits, as well as issues around site selection and scale. Both presentations highlighted the importance of community involvement, clear information, and integrating place-based approaches to improve acceptance and increase the chances of successful implementation of these innovative practices.

Ruedi Kriesi, Alexandra Doernberg, Siddharth Sareen, Ricardo Filipe and Pascal Vuichard (University of St.Gallen) in the first breakout session.

After each breakout session, the group reconvened to share insights.

The participants then returned to their smaller groups to discuss what they had heard and to explore ways to facilitate innovations for fair and acceptable projects more broadly. One of the conversations centered on the practicalities of participatory landscape design. The biggest obstacle was seen as the lack of incentives for developers to invest in a lengthy, uncertain process with no guarantee of a socially acceptable outcome.

It was suggested that participatory design—like sustainability—could be included as a non-price criterion in renewable energy auctions, but that this would introduce complex questions of accountability and measurement. Who would evaluate whether participation was meaningful? What qualifies as an inclusive, sustainable or well-integrated project? Discussions such as these underscored some of the systemic barriers to innovation in large-scale solar deployment, revealing how economic priorities, regulatory structures, and political dynamics shape the possibility of change.

The fourth session of the day began with presentations from Rachel Hayes (Solar Energy UK) and Elif Gündüzyeli (The Nature Conservancy), both of whose organizations have recently published good practice guides aimed at a range of different stakeholders involved in the deployment of large-scale renewable energy technologies. Rachel introduced Solar Energy UK's Community Engagement Good Practice Guide, focusing on its development process, key recommendations, and its role in shaping effective stakeholder engagement for large-scale solar projects. She highlighted specific tools and strategies outlined in the guide that had proven successful in fostering community acceptance.

In addition to providing an overview of The Nature Conservancy's Enabling a Community-Powered Energy Transition white paper, Elif discussed their work developing a public participation GIS tool, showcasing how spatial analysis could enhance community engagement and inform equitable project siting. Both of these presentations demonstrated how NGO’s are mobilising social scientific knowledge and co-designing innovations that can contribute to a fairer and more acceptable deployment of solar energy infrastructure.

Kaya Schwemmlein (University of Lisbon) summarises her group's discussion. The online group also included Luís Silva (NOVA University Lisbon), Josefa Sánchez Contreras (University of Granada), and Alberto Matarán Ruiz (University of Granada).

David Rudolph (DTU), Rachel Hayes, Susanne Hanger-Kopp (ETH), Ana Rita Antunes (Coopérnico) and Doug Bessette.

In the concluding plenary discussion, participants reflected on key tensions that emerged throughout the day. A central debate focused on the contrasting cases of Switzerland and Portugal, raising the question of whether political culture or political economy plays the defining role in shaping community acceptance and energy justice outcomes. While Switzerland has a strong tradition of direct democracy, the situation in Portugal is markedly different. As one Portuguese participant noted, “in general, we don’t have a participatory culture. It’s not valued, and there isn’t enough knowledge within public administration to conduct these kinds of processes. In fact, it’s actively avoided.”

Another key issue raised was the gap between laws promoting sustainability and public participation and their actual enforcement. In many contexts, despite the existence of such laws, violations occur frequently. This underscored the need to establish stronger accountability mechanisms.

The discussion also highlighted tensions between centralized, top-down governance and decentralized, bottom-up approaches. While some countries, such as the UK, are now aiming to more systematically coordinate local planning at the national level, others argued that framing the energy transition as a top-down imposition fuels resentment, particularly in rural areas. Terms like “social acceptance” and “green transition” can even become, as one participant put it, “triggering” for these communities.

This perspective pointed to the politics of knowledge production in social acceptance and energy justice research, emphasizing the importance of academic work remaining independent of commercial interests. It also reinforced the need for research to be conducted with and for place-based communities, rather than merely about them.

Rachel Hayes presents Solar Energy UK’s Community Engagement Good Practice Guide.

The workshop consisted of individual presentations, small breakout sessions, and full-group discussions.

The conversation culminated in a fundamental question: Who is the ‘we’ in our normative visions of the energy future? While this provoked different responses, it was quite clear that whether it is the perspective of technical experts oriented to policymakers or critical scholar-activists working alongside communities-of-relevance, the challenge remains the same – to effectively translate and communicate these visions to the decision-makers who are currently shaping national and international energy trajectories.

In sum, the CAREsolar workshop brought together diverse expert perspectives for a productive dialogue on community acceptance and energy justice in large-scale solar projects. However, this conversation is only the beginning of a broader collaboration aimed at developing a new conceptual framework and practical recommendations. Alongside publishing the systematic literature review, the next steps will be to analyse and map the workshop’s wide-ranging contributions.